SHACKLETON MEDAL 2025: MEET THE SHORTLIST - TWILA MOON

Climate Scientist and Science Communicator

As lead editor of NOAA’s Arctic Report Card, Moon coordinated 97 scientists across 11 countries to assess the state of the Arctic in 2024 - concluding that the region is now emitting more carbon than it stores. Her work bridges climate science and policy at the highest levels.

You were lead editor of NOAA’s 2024 Arctic Report Card, which this year made the dramatic announcement that the Arctic has turned from being a carbon sink to a carbon source. What did you need to do to put it together?

The Arctic report is an incredible effort. There are many areas in which I do polar, Arctic-related communications work where I’m working mostly on my own or with a smaller team. The Arctic report part is the other end of the spectrum – we have so many people who are contributing and making it happen. So as well as myself as the year's lead editor, there are two other independent editors. We have people on the NOAA side who are working on the website and the video and the comms and many other elements. And then, of course, we usually have somewhere around 100 different authors who were coordinating their contributions and working with climate.gov to help assist and get good graphics. Something I have really worked on in my time with the Arctic report card is introducing new graphs and graphics to pull the information together. We’re always trying to find new ways to make the information clear and disseminate it as widely as possible.

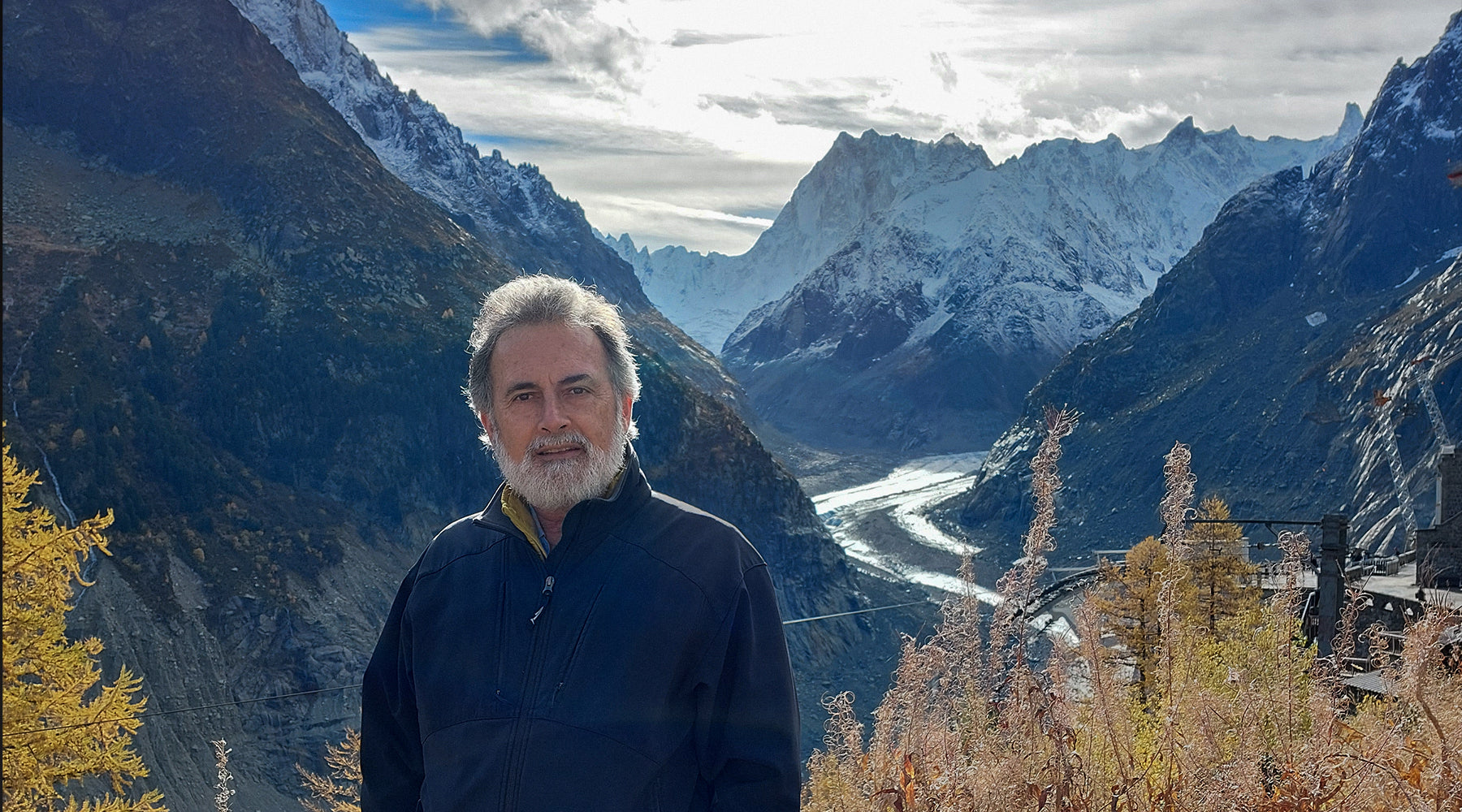

All polar scientists have to be very physically brave as well as intellectually brave – able to navigate extreme landscapes. You’ve done a lot of work in Greenland. Can you talk about what you’ve done there?

I grew up being outdoors. I encountered my first big mountain glacier in eastern Nepal, and that's when I fell in love with ice, at a time when, scientists were just starting to get the first data that would tell us how rapidly the Greenland and Antarctic ice sheets were changing. So in some ways, I feel like I was among those last people who got to just fall in love with ice without it being so totally connected to climate change.

It was at the onset of graduate school that I got to work with Ian Joughin [the University of Washington-based glaciologist who is working to determine how the flow of the Greenland and Antarctic ice sheets will contribute to current and future rates of sea level change.) We were receiving initial data that showed us, for instance, how is the edge of the ice sheet changing for Greenland on that scale? What do changes in motion and velocity of the ice look like at that scale? I loved getting to look at an ice sheet at scale, but still see it in detail, and those were, of course, pretty jaw dropping results in regard to how quickly the motion of outlet glaciers in Greenland could change and how substantially the glaciers were already showing retreat in places all around the ice sheet.

The very first time I did field work in Greenland itself, we were up on these lakes that form on the surface of the ice sheet. We succeeded in setting up all these instruments in Lake Number 1 and then we were transferred to Lake Number 2. So we got there, and then the fog came in. Before we got any science instruments, we spent five days just sitting in our tents, talking to each other, wishing our science instruments were there, and then they didn't get delivered.

So when they eventually came, the only solution was to sleep as little as possible to get things set up, so we could actually get instruments going, have things running, so that we could leave the field having accomplished the science. There are plenty of challenges in the field.

When you’re talking to people about your research, how do you wake them up to the fact that what happens in the Arctic impacts on the rest of the globe?

Whenever I give a talk or a workshop, I tie things that happen in the Arctic or at the poles directly to us where we are. So if I'm giving a talk in Idaho, in the very middle of the Northern America, I'm going to take the time to tie changes in Greenland, to things happening in our coast, to how we maybe move goods that are produced in Idaho. I ran a workshop in Washington State last week, so I was talking about changes in the Arctic, and how they connect to the changes in atmospheric rivers that are felt in Washington State, or how the Arctic is influencing winds and weather patterns to produce unprecedented, long lasting heat waves right there. I always take the time to give people agency in searching for solutions as well. So I help them realise that if I'm going to address food waste with my local school system, that is going to do things right there for me, and it's going to do something for ice that is far, far away from me, because we have these intrinsic ties that connect us.

Which aspect of your work is most important to you?

The area in which I hope to change the culture of science is in climate science communication. It's some of my highest impact work. I have generally done this work – as almost all scientists do – as a cherry on top, in my free time, out of passion, and I feel like that's been possible for me because of any number of ways in which I'm privileged. I'm not caring for children or elderly people, I have a supportive spouse. All of these things have allowed this, and I really think that has to change. So I have been working for many years to have an institution create a research scientist position where part of the definition of being a research scientist is communicating the climate science outside of academia, with people who need this information, and for whom it is important to get it from a scientist. I received a go ahead from my institution to create this. And then, because of the federal funding chaos, I wasn’t sure it would happen. But it did. April was the first month where, as a research scientist, I have a job description that says, This is important work, and you need to be doing climate science engagement. My hope is that I can make this super successful.

What are your ambitions for the coming year?

We will have a 20th anniversary Arctic Report Card. There will be a few extra bonus things that will happen during the year. There's a photo video contest, if people want to participate, throughout the year, interviews with people who have been a part of it, and other extra events. Of course, it’s especially important because NOAA’s Arctic Report Card is under threat because of US federal funding cuts and the administration’s priorities. So I think this is an especially important time to be talking about this, particularly in the US. I did some work in January with congressional meetings to help emphasize how the Arctic is important to the US lower 48. There's never been a more important time in the US for helping people understand how we're connected to the poles and how important our environmental awareness of these places is.

By Rachel Halliburton