A Titan of Polar Exploration

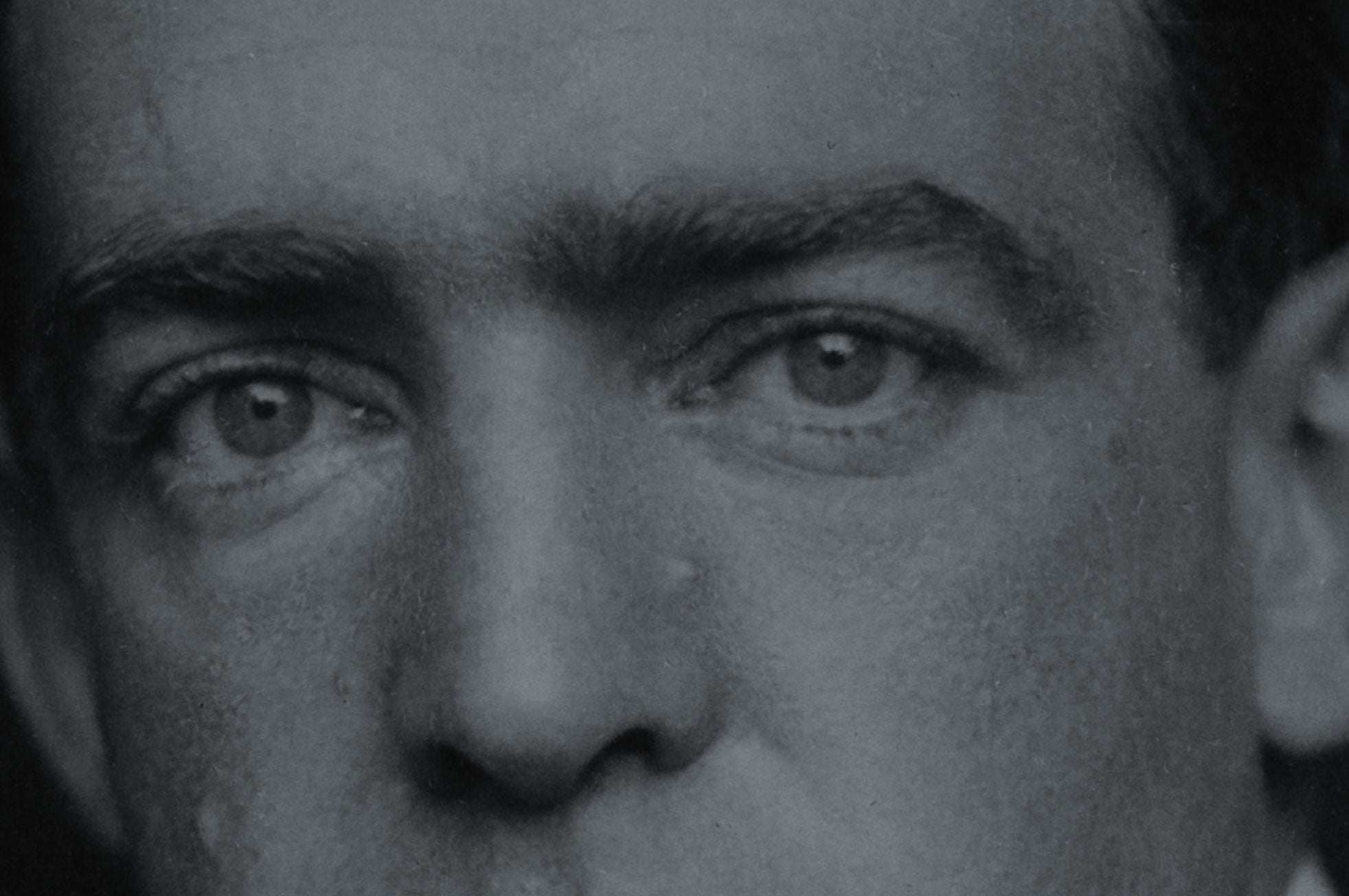

Legendary explorer Sir Ranulph Fiennes explains how Ernest Shackleton has been a driving force behind his own ambitions.

Ever since I was a small boy at school in South Africa, I’ve studied the 19th century explorers – particularly the British – who spent a lot of time looking for the source of the River Nile, and the early 20th century British explorers trying to go far south or far north into the icy places they knew existed but knew nothing about.

I journeyed to the source of the Nile myself. Then, after being in the British Army and the SAS and fighting Communist rebels in the Dhofar War, I moved on and started looking more carefully at the histories of people like Shackleton, Scott and Amundsen, and others who had died during Antarctic expeditions.

The one who stands out a mile for persevering in the face of abominable luck was Ernest Shackleton, whose life – and death in 1922, almost 100 years ago – I have scrutinised with great care.

Shackleton wanted to be the first to cross the continent of Antarctica, made up – in part – of ice floating in the sea, semi-attached to the actual land. He made a number of expeditions that never succeeded in reaching the South Pole, but set incredible records as he came increasingly close, without ever actually accomplishing his goal. Yet he is rightly famous for having undertaken an astonishing rescue mission during his 1914-1917 Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition.

Shackleton’s ship, the Endurance, set sail from Buenos Aires to drop him off at Vahsel Bay. His plan was to march towards the South Pole and – if still alive when he got there – proceed to the Ross Sea along the route Scott and Amundsen had already taken to reach the pole. To facilitate this 1,800-mile trans-continental journey, another ship – the Aurora – would land at McMurdo, from which the Ross Sea party would travel to lay depots along the proposed route of the trans-atlantic party in order that Shackleton and his six companions could complete the second leg of their march from the South Pole to the Ross Sea.

Thanks to an ongoing collaboration between The Royal Geographical Society (with International Bureau of Geographers) and Salto Ulbeek Publishers in Belgium, the unique opportunity to purchase from the first ever collection of limited edition platinum palladium prints of ‘Endurance’ expedition is now available.

The plan never came to fruition. Endurance became icebound in the Weddell Sea en route to Vahsel Bay and drifted northward before finally sinking in 1915. The ship’s crew were stranded on Elephant Island, forcing Shackleton to mount an extraordinary rescue mission – setting out in a small open boat called the James Caird and sailing 800 miles to the inhabited whaling station of South Georgia. From there, on the fourth attempt, he successfully returned with a volunteer team to save the 22 remaining crew of Endurance, in what remains one of the most daring rescue missions ever documented.

Since then, Shackleton’s critics have claimed that had his ship not sunk and he had set out as planned, he would – taking his fuel and rate of progress into account – have been mathematically unable to complete his journey, and would have died trying; ergo better that his ship had sunk. That’s a horrible criticism, and it took 50 years for someone to prove that Shackleton’s plan could – and probably would – have succeeded.

In 1993, I set out to see if Shackleton could have achieved what he wanted to; becoming the first to cross the Antarctic continent on foot. I ran the expedition with Britain’s top food stress nutrition expert, Mike Stroud, who based our dietary plans on Shackleton’s and Scott’s own plans for their rations. We knew that at the end of every day we had to have travelled 16 nautical miles; if you get diarrhoea en route, you carry on. When you face blizzards, like Shackleton and Scott did, you carry on. You don’t stop, because if you do you will never catch up 32 miles the next day. We nearly died before we got to the South Pole, and when we got there I told Mike I didn’t think we should carry on; it would be asking for trouble. Nevertheless, we forged on to complete the crossing, arriving at our destination almost dead.

When I got home I found I’d lost 55 pounds despite eating 7,000 calories a day – but we had proved mathematically, without a doubt, that Shackleton’s plan would most likely have succeeded.

Shackleton admitted at all points – and this is quite unusual for successful explorers – that a huge ingredient of his expeditions, successful or otherwise, is Lady Luck. Explorers don’t like admitting: “Oh well, we were lucky.” They like saying: “We were clever, we got it right.” Shackleton looked very carefully at his predecessors to see where they’d gone wrong – as we did when we set out – and one thing he always tried to do was avoid risks where he could see them, rather than aim to overcome them. He would never panic, and he always believed that Lady Luck – who he called Provi, short for Providence – would go his way in due course.

Shackleton inspires us to never say die. His endeavours impel us to realise that Lady Luck – or Provi – is always just waiting around the corner; that even when our circumstances appear most dire and deadly, everything can still go right if you stick at it and remain calm.

Lead image by Gary Salter