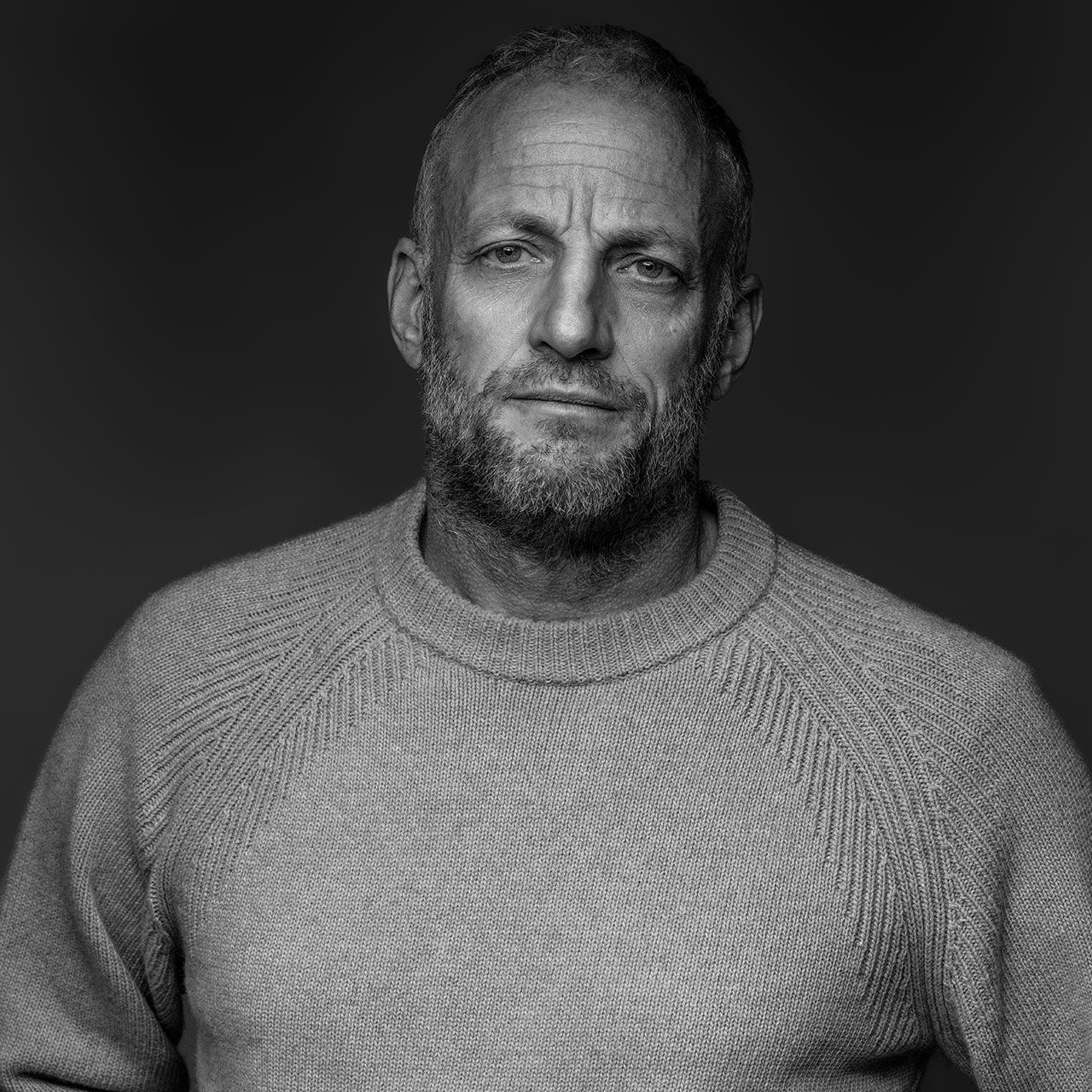

PHOTOGRAPHER. POLAR EXPLORER. CLIMATE ADVOCATE.

Over the last 20 years, Martin Hartley has demonstrated a pioneering spirit and remarkable courage in extreme environments, photographing desert journeys across Oman and Yemen, the Empty Quarter, and the Himalayas in winter. His work has taken him to both the North and South Poles, collaborating with scientists on and under the sea, and working with anthropologists around the world. His photography captures the beauty and fragility of some of Earth’s most challenging landscapes, including deserts, mountains, jungles, oceans, and polar ice caps.

TIME magazine recognised Hartley’s dedication and bravery by nominating him for a Hero of the Environment award, honouring his work documenting the rapidly changing Arctic sea ice on numerous surveys, including NASA’s IceBridge project. This recognition, along with his inclusion among the world’s top 40 nature photographers, reflects his commitment to documenting the natural world.

Hartley has also taken on ambitious assignments for National Geographic, including a journey retracing the historic Frankincense Trail, driven by his relentless curiosity and dedication to exploring the planet’s most unforgiving environments.

ENVIRONMENTAL ADVOCACY

“My aim now is to use my photography to educate people on the importance of the environment and to encourage them to protect it by changing their behaviours.”

THE STRANGEST POLAR ASSIGNMENT EVER

At first, he thought it was a joke. He had received an email from the PR agency for the Football Association, and his initial reaction was, “This can’t be real.” They wanted an adventure photographer to capture the journey of fans on an FA Cup qualifying day, focusing on the supporters’ experiences rather than the game itself - which suited him perfectly, as he wasn’t a football fan.

The meeting took place on a Monday, and Hartley was scheduled to fly to Cape Town that Saturday to head for the South Pole. Half-jokingly, he suggested, “Why don’t I take the FA Cup to the South Pole so it can have its own adventure to kick off the campaign?” Everyone laughed, but then, on Thursday night at 11 p.m., the head of the PR agency called and told him, “Martin, if you can get the FA Cup insured, you can have it.” Hartley immediately called a former sponsor from one of his Arctic expeditions, who agreed to insure the Cup. So, he set off for the South Pole - with the FA Cup in tow.

When he arrived at Heathrow Airport, the reality of his task began to sink in. A large, tattooed man approached, took the FA Cup out of its shiny case for a quick photo, and asked, “It’s going on the seat next to you, right?” Hartley replied that it was going in the hold, but the man shook his head, explaining, “No, that cup has never traveled out of the country without a ticketed seat beside someone.” Then he walked off, calling Hartley an idiot.

Hartley found himself pushing the FA Cup around in a food barrel, sweating as he realised he was effectively carrying the crown jewels of football. At one point, the police stopped him and asked what was in the blue barrel. When he told them, they didn’t believe him, so he had to show them the FA Cup wrapped in an old green sleeping bag before they finally let him through security.

DOCUMENTING DISAPPEARING CULTURES

“In India, I documented a way of life that’s now gone… Looking at those old photographs now, I realise they have a cultural and social value that’s really significant.”

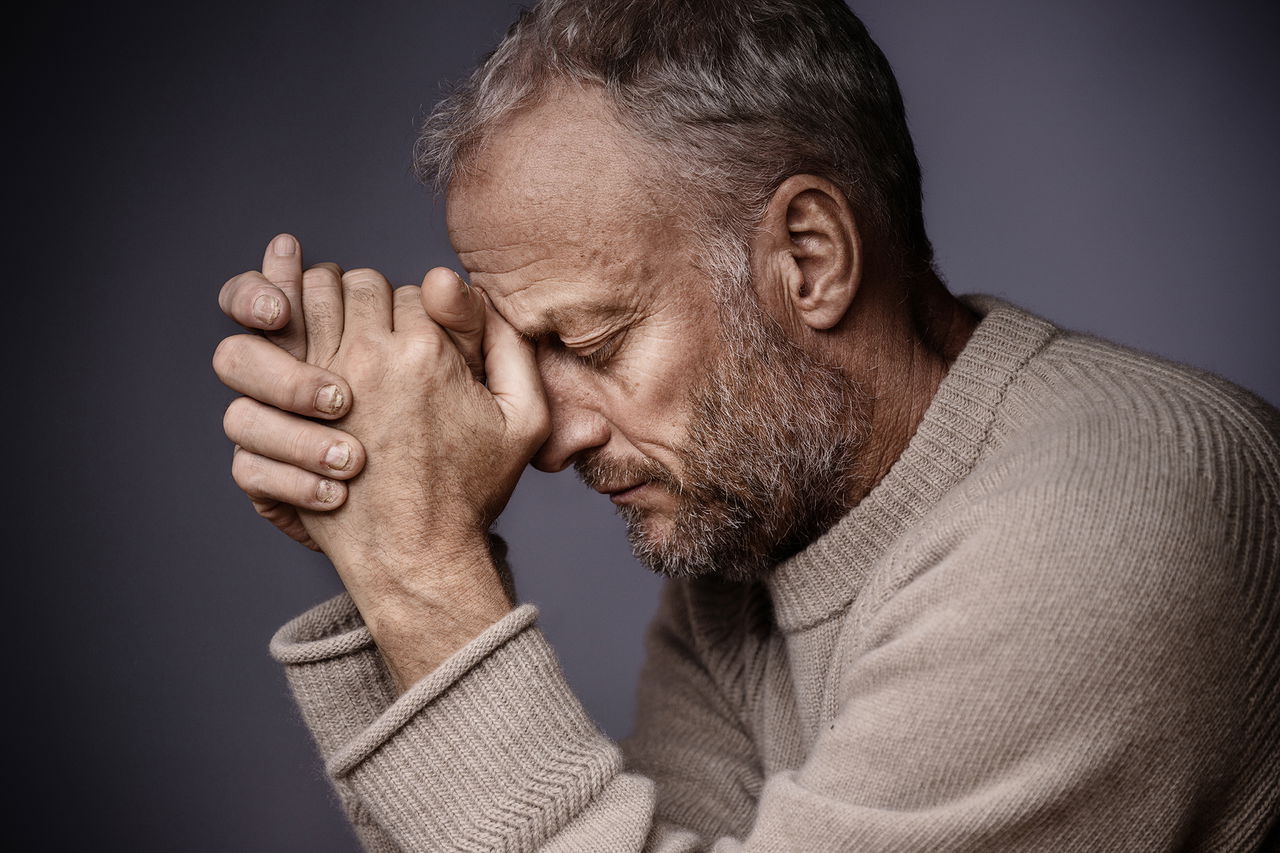

TO CARRY ON OR TO TURN BACK

One of the toughest situations Hartley has faced came during a 100-day expedition on the Arctic Ocean. Just three days into the journey, he developed frostbite. When he removed his socks, he saw his toes had turned an aubergine colour - a sign of severe cold damage. He was faced with a quick and difficult decision: either arrange for an extraction to save his toes in a hospital or continue with the expedition and hope for the best. It was early in the journey, at the coldest time, and he thought, "If I’m going to lose my toes, I might as well lose them out here rather than lying in a hospital bed feeling sorry for myself."

Once he decided to stay, everything became mentally easier, even though the physical challenges remained. But each day, the biggest hurdle was simply putting his boots on. He knew he couldn’t let his toes get cold again or risk infection, so the weight of that decision followed him constantly. Every night, he worried if his toes would survive, but he surrendered to the mission's purpose - documenting the sea ice over many miles and days. The choice to stay had been tough, but with that settled, he found he could manage everything else.

Amelia Steele (Interviewer): “Bloody hell. So, did you end up losing your toes?”

Martin Hartley: “No, actually, I still have them all. I was lucky. My teammate, Ann Daniels, tended to my feet every night in the tent, carefully changing the bandages and cleaning them, making sure they didn’t get refrozen.”

READ THE INTERVIEW

MARTIN'S KIT BAG