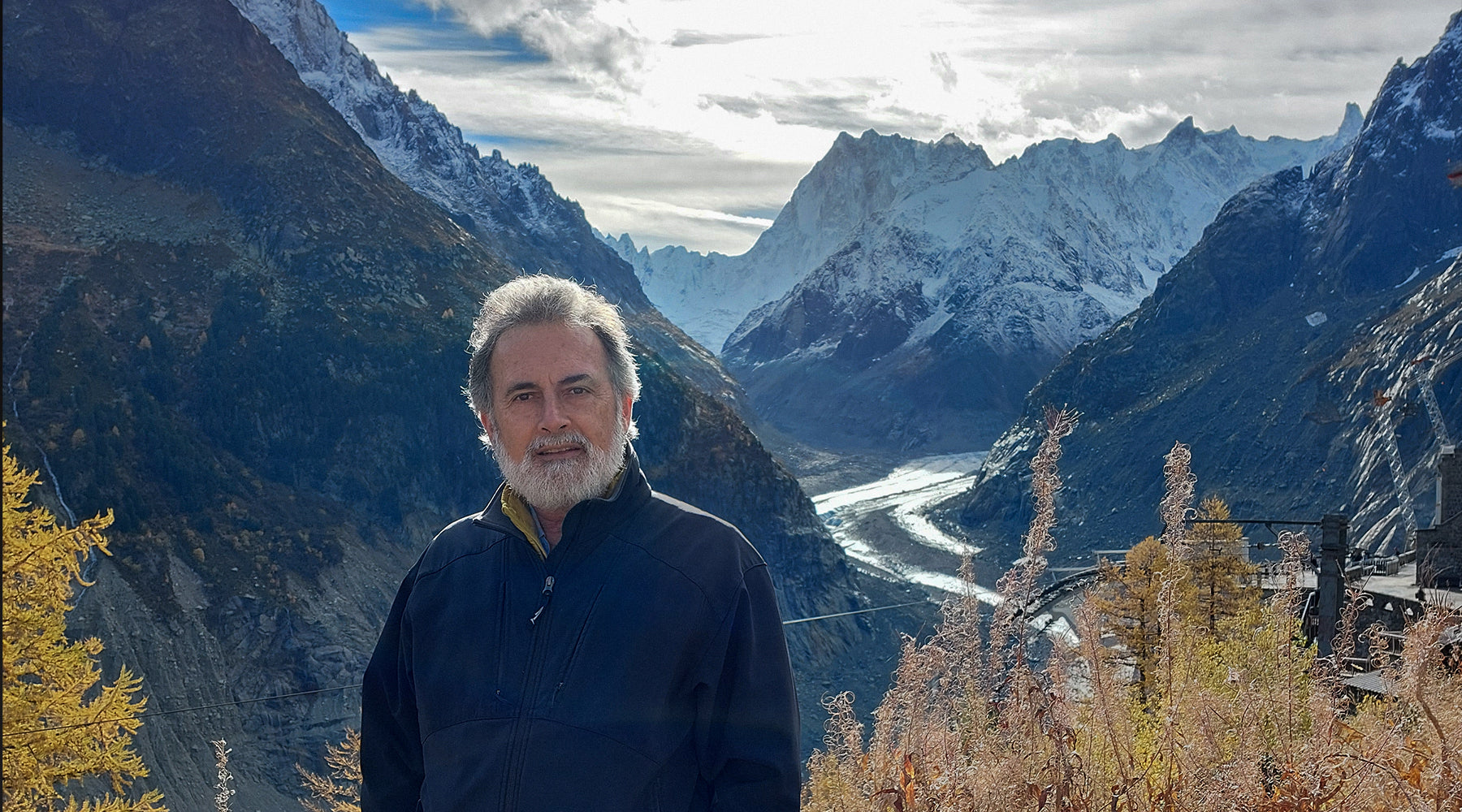

SHACKLETON MEDAL 2025: MEET THE SHORTLIST - CORMAC CULLINAN

Environmental Lawyer

Through the Wild Law Institute, Cullinan is driving a legal revolution: advocating for Antarctica to be recognised as a rights-bearing entity under international law. His Antarctic Rights Initiative seeks to grant the continent the right to remain wild, undisturbed, and free from exploitation.

You published your seminal book Wild Law: A Manifesto for Earth Justice – which proposes recognising natural communities and ecosystems as legal entities – in 2003. It was a revolutionary concept at the time. Can you explain what led you to write it?

For a long time it’s been clear to me that if you were an alien visiting this planet, you would quickly realise that the big issue is how just one species is changing the environment. So how that plays out is a major concern. I decided that becoming an environmental lawyer would let me play a role in solving the problems surrounding that. I set up a consultancy firm and – with my colleagues – did work for a lot of countries and tried to draft as much legislation and policy as I could, because I thought that would have a big impact. But then it became obvious that there were problems I wanted to solve that couldn’t be dealt with by better drafting.

As I was chewing this problem over, somebody put me in touch with Thomas Berry (a Catholic priest who was one of the earliest and most influential thinkers about humans’ relationship with the planet). He said to me “We need a new philosophy of law, because our legal system doesn’t take account of nature as a subject at all”. It was the equivalent of giving me the end of a piece of string which I then followed. I suddenly realised that the situation could be compared to when slaves were treated as objects that could be bought and sold. Here Nature is the slave – and it’s exploited just in the same way that slaves were exploited. That was a real eye-opener to me, and it led to me writing Wild Law.

When it was first published, it was considered very alternative – the kind of book that if you were reading it in a law firm, you might almost cover with a brown paper bag! Now, all this time later, even Harvard Law School has got a course on it – so it has become a part of legitimate academic discussion.

You have been shortlisted for the medal because of your Antarctic Rights Initiative which seeks to grant the continent the right to remain wild, free and undisturbed from exploitation. How did this come about?

When I started thinking about Antarctica, I really got very excited about it, because I realized that this is a whole new ball game. First of all, nobody owns Antarctica – apart from the high seas, it's the only big part of the globe that's not owned. Everybody went down and stuck in their flags, but that colonial process was never completed. Until I started considering it in depth, I’m ashamed to say I also didn't appreciate how big and important Antarctic was ecologically. The Southern Ocean covers 6% of the surface of the plant, it drives all the ocean currents and absorbs CO2, so it's completely unique ecologically and incredibly important to the stability of the climate, but at the same time hammered by climate change. I realised that the Antarctic Treaty System only applies within the treaty area, but most of the harm relating to climate change is originating outside the treaty area.

Normally people would say, well we have other mechanisms for dealing with climate change – such as the UN and the Climate Change Commission. But the Antarctic doesn’t really have a voice, partly because it doesn’t have an Indigenous population. Even if people who were part of the Antarctic Treaty System (ATS) were to represent Antarctica, it’s a club of countries that includes some of the biggest polluters in the world! Even within the ATS they argue for their own interests. Nobody’s making decisions about Antarctica based, really, on what’s best for Antarctica. So I thought, we’ve had rivers and forests recognised as legal persons subject to the law at national levels. But Antarctica would need to be at international level. It’s a whole step up. If we could get its status to at least that of a country, then it could be represented at the UN or in court.

What have reactions to the initiative been so far?

A lot of people in the Antarctic Treaty System love the idea because the system is so stuck. Nothing gets passed. You require consensus to pass anything. You’ve got Russia and Ukraine in there for example so you can imagine how much consensus there is. So everything is completely stuck and it’s not going to get changed from within. I think the only way to progress is to exert pressure from the outside. It looks as if countries like Russia are thinking of mining it after 2048 when they can renegotiate the treaty – or possibly sooner. I don’t know if they’re willing to break the treaty.

I think the best way to deal with this is to get a lot more people on the side of Antarctica. For instance, in Africa only South Africa is part of the ATS. But climate change hits Africa harder than anywhere else, and once other countries wake up to the fact that Antarctica should matter to everybody then they’re also going to be looking for new ways forward. Most of the world – at state level and also people level – are shut out of the ATS. So we’ve got to mobilise the whole of that constituency, as well as people in the ATS. Some people love the initiative within the ATS because they feel it’s a breath of fresh air and it’s going to get things moving. And some people are resisting it because they see it as undermining their claims. For instance, some Australian academics are saying it’s undermining Australia’s sovereign claims. But I think you’ve got to draw a distinction – are you defending Antarctica or are you defending the ATS? I think the ATS was a wonderful achievement at the time. But if it’s not working well enough – and we can see it’s not going to save Antarctica – we have to take risks and do something more.

In your work, you’re very committed to bringing in an Indigenous perspective. Can you describe how that works with Antarctica?

I originally assumed that it wouldn’t be relevant. Then I read that the Maori people have stories in their Cosmology about discovering a white land. Since then I’ve realised that other people – like the Polynesians – don’t have a direct connection, but have a cosmology in which Antarctica is seen as part of the body of the world and plays a role. Indigenous Americans have told me that in their “Original Instructions” they had an understanding that their responsibilities extended from pole to pole. All of this really amazed me to be honest.

We went to the World Wilderness Congress in South Dakota and I went to promote this idea. They passed a resolution in support of us and now we want to move it up to the next level, which is the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Conference happening later this year in Abu Dhabi. We needed sponsors who are IUCN members. One of the organisations that stepped forward to sponsor us was a group called CONAIE, which is a large group of Indigenous peoples of the Amazon. So though they seem very far removed from it, people in the Amazon understand the importance of Antarctica because they view Mother Earth as a whole.

You’ve been passionate about the outdoors since you grew up in Pietermaritzburg and spent a lot of time outside.

One of my strongest memories is from when my father organised for a Zulu guide to take myself, my siblings and him on a wilderness trail walk. There were elephants and lions and everything and we were just on foot and we slept out. My girlfriend at the time was a botanist, and she was always grabbing plants and picking apart the leaves and explaining them taxonomically. But our guide would look at a plant and say, “This is what we use this for”. It was completely practical cultural knowledge. He also understood how to deal with the animals. Experiences like that were absolutely seminal for me. Even now I think it’s important to spend as much time in nature as possible.

Has Shackleton’s story impacted on you at all?

When I’m thinking about what’s happening to Antarctica, I sometimes think it’s comparable to what would happen if you took a block of ice out of your fridge and put it on a table. Once it starts melting, you can't stop it unless you get the temperature in the room below zero. The ice has started melting and, and, you know, it might take 200 years or a very, very long time to melt, but there's a terrifying inevitability about it. I think that story about Shackleton – where he and his men were coming over the mountains on South Georgia Island and he realised they were up too high and would die if they didn't get down soon – is really instructive. They defied the odds by creating a makeshift rope sledge and sliding down. Though the sensible thing would have been to go down very slowly, they would have died that way. So even though the chances of surviving sliding down the mountain were low, they were more than zero.

For me that’s like an analogy for these times. The most dangerous thing we can do is not to be courageous, not take risks, and not be innovative.

By Rachel Halliburton