Shackleton at the BFI

Shackleton is proud to partner with the British Film Institute for the screening of the film 'South: Sir Ernest Shackleton’s glorious epic of the Antarctic’. At the premier at the BFI IMAX on January 27 this new, digitally remastered version will be accompanied by a live orchestra. This is the story of the film and the intricate process of digitally remastering it for the twenty-first century.

Using film to make history

In 1919, tens of thousands of people flocked to watch films about two very different men who had survived against the odds in two very different deserts. One of them, Ernest Shackleton would become synonymous with pushing the boundaries of human experience in Antarctica. The other, T E Lawrence, would go on to play a part in redefining the Middle East. Though film was in its infancy, both men knew that the movie camera was the best way to ensure they would go down in history. Apart from anything else, it provided proof in an increasingly scientific age that the heroic protagonists had done what they claimed to.

The earliest form of multimedia

Though it may seem counterintuitive now - at that point film on its own was not seen as the most powerful way to tell a real-life story. Documentary had not fully evolved; so both South and With Lawrence In Arabia started out as live talks accompanied by ‘lantern’ shows – in which images from glass slides were projected onto a screen. ‘Lecturing was more lucrative than releasing a film,’ says Bryony Dixon, the curator of silent film at the BFI who has overseen the new digital remastering of South. ‘It seems extraordinary now.’ Though this was a time where Dickens’ popular recitals of his novels was within living memory, where the charismatic orator would occupy centre-stage for decades to come. There was also the added bonus of flesh and blood authenticity. In the lantern shows about TE Lawrence, the performer was an American, Lowell Thomas, who had personally filmed Lawrence in the Middle East. For those initial shows about Shackleton, the lecturer was the man himself.

‘For audiences watching "South" it would have been the same as we felt seeing those Perseverance pictures from Mars.’

To have the chance to watch South at the BFI IMAX, then, is not just an opportunity to witness Frank Hurley’s astonishing film footage and photography of what happened to Shackleton and his men in the Antarctic. It also provides an insight into the working methods of an expedition leader who was as much a showman as an explorer. Ranulph Fiennes’ Shackleton: A Biography opens with an account of the young boy telling his sisters that during a trip to London he and a friend had tackled a ‘raging inferno’ and had been rewarded with the building of the Monument in their honour. (Was, you wonder, 1666 on that term’s history syllabus?) Those storytelling abilities would prove intrinsic not just to his charisma as a leader but to his ability to raise money. When he and other members of his crew gave their talks about the Antarctic, Shackleton knew that the images on display in South would simultaneously bring the visceral immediacy and technological va-va-voom that would encourage audiences to reach deep into their pockets.

Frank Hurley and Heroic Photography

It’s telling that Hurley was the only member of the 'Endurance' expedition who Shackleton recruited without a face-to-face encounter. The Australian’s reputation had been established when he had worked with Douglas Mawson on the 1911-1913 Australasian Antarctic Expedition. Lionel Greenstreet, first officer of the Endurance, described him as ‘a warrior with his camera [who] would go anywhere or do anything to get a picture’. Shackleton only wanted the best; he had registered the Imperial Trans Antarctic Film Syndicate before leaving and recognised that Hurley had both the talent and the bullish personality to realise his vision.

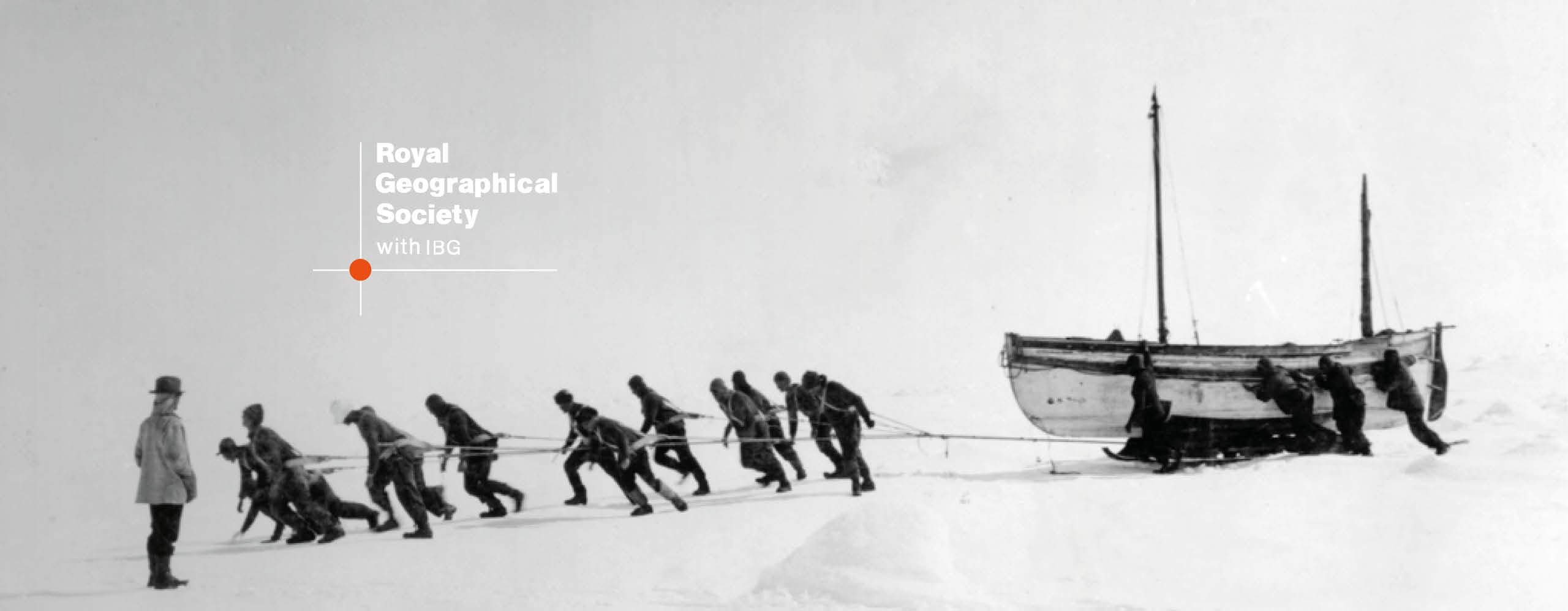

More than a century after the images were created, it’s impossible not to feel the jaw-cracking immediacy of scenes that are now the stuff of legend. Hurley’s stills of the Endurance trapped in the ice were taken at night with magnesium flares used as lighting. When you see the tilted ship, with its masts stabbing into the sky as the ice devours her, the fact that the men survived the ordeal seems even more remarkable. Beyond this Hurley deployed his full genius to allow audiences to experience both the beauty and the terror of the alien Antarctic landscape, skilfully interchanging close-ups with long-shots. The austerity of such detail is in counterpoint to the more informal footage of a crew trying to assert some kind of normality on a continent that to date had resisted any form of human settlement.

An afterlife on celluloid

It’s particularly sobering, watching the footage from South, to realise that the then most recent images to come back from the Antarctic – shot by the other great photographer of the Heroic Age of Exploration, Herbert Ponting – had been from an expedition where the leaders had ended up dead. Although images of Scott on his last quest to the South Pole had first arrived in Britain as documentary, as news broke of his fate, the photos were reissued with black borders, in the style of mourning stationery. To what extent was this on Hurley’s mind when - according to his own legend - he stripped to the waist and dived into the icy waters engulfing the Endurance to save his precious photographic glass plates? To what extent did it help him with his calculations when he realised he could only take 150 of more than 600, and needed to smash the rest, not certain at that point whether his work or his expedition colleagues would ever see civilisation again?

The intricate puzzle of putting the film back together

The new version of South has a score composed for it by Neil Brand, which will be performed by a live orchestra at the premier. It’s the crowning glory of a version that has demanded incredible skill from a dedicated team to put it together, not least because – as Dixon points out – its origin as a lecture means that ‘you have to piece it together like a jigsaw because there’s no script.’ The footage used by the BFI comes from prints released in the early twenties – used for lectures by other members of the Endurance crew - that were remastered for a sound version in the 30s. Part of the art, she explains, is to upgrade the images but ‘not to over-restore them; you want to reflect the artefact and the sense of the celluloid – you want to leave that sense of history.’

The equivalent of the Perseverance Rover on Mars

One of the more startling aspects of the film is that following the build-up to the drama of the sinking of the Endurance, there is a lengthy period focusing on the wildlife of the Antarctic. ‘One of the big issues in terms of the film,’ says Dixon, ‘is that Frank Hurley didn’t know precisely what story he was going to be telling in terms of the rescue.’ Hurley was not one of the men who went with Shackleton on the James Caird to South Georgia. So he could not capture the dramatic voyage and the walk across the mountains to the whaling station at Stromness.

'We can, just for a short time, be there with Shackleton, watching as the Endurance sinks beneath the ice'

What he could and did do was relay to audiences a sense of other things they had not witnessed. ‘Most people in the audience back then would only have ever seen a drawing of a penguin. As we all know the important thing about penguins is how they move,’ she observes. The owner of the rights of the film was in no doubt about the importance of such detail. ‘After everything Hurley had been through, he was sent all the way back to South Georgia to film the wildlife. It was exciting because it was new. It was the same, in a way, as the way we felt seeing those Perseverance pictures from Mars.’

A historic opportunity

It’s a testament to the skill with which Hurley captured those images that they will be able to be displayed at the IMAX. Possibly it’s only seeing them on this scale that can convey with full force the beauty and the hostility of the landscape that almost destroyed Shackleton and his men. An extraordinary opportunity, then, for both polar enthusiasts and devotees of cinema history. Proof too, that Shackleton’s gamble was right; that in the centenary of his death we can, just for a short time, be there with him, watching as the Endurance sinks beneath the ice.

The remastered BFI restoration of SOUTH is released in select UK cinemas from 28 January and features on a special 3-disc Blu-ray/DVD set, released on 28 February, SOUTH & THE HEROIC AGE OF ANTARCTIC EXPLORATION, which collects for the first time the surviving films from the Heroic Age, sourced from archives around the world, including footage from the Amundsen, Mawson, Shirase and Shackleton expeditions from the early 20th century.

Pre-order info here: https://shop.bfi.org.uk/south-the-heroic-age-of-antarctic-exploration-on-film.html